The Campbells in Scotland

The origins of Clan Campbell, like most Scottish clans, are obscure. We are said to be descended from Clan McDuibne and the first recorded Campbell was Gillespic or Archibald Cambel, who flourished around 1260 and died around 1280. There are several more romantic stories about the origins of the Campbells, but we can discount these. The early history of the Campbells can be found on Wikipedia, Scotweb, Electric Scotland or in many other online sources (which don’t necessarily agree with each other), and there is a recent 3 volume history of the Clan by Alastair Campbell for those that want to delve deeper.

Gillespic’s son was Colin of Lochow, who was knighted by Alexander III. Sir Colin greatly expanded the Campbell estates and was known as Calein Mor or Great Colin. His descendants, the Dukes of Argyll, still style themselves Mac Calein Mor.

Glenorchy

The seventh Campbell of Lochow was Sir Duncan, who conferred the lands of Glenorchy on his second son Colin in 1432. The lairds of Glenorchy carried on the Campbell tradition of expanding their lands at the expense of their neighbours, and by the 1560s and 70s his descendant Duncan, 7th of Glenorchy, known as Black Duncan (the self-confessed “blackest laird in all the land”), completed the conquest of Upper Glenorchy from Clan McGregor. One of the McGregor holdings that Duncan took was Achinnis Chailein, which was eventually shortened to Auch.

Barcaldine

Duncan married twice and had numerous children, including as two sons by his mistress Janet Burdown, Patrick and James, who were legitimated under the Great Seal of Scotland in 1678. Duncan established Patrick on lands at Innerzeldies in Perthshire and at Barcaldine Castle in Argyll. Patrick was known as Para Dubh Beg, or Little Black Pat. Patrick’s son was John of Barcaldine whose second wife was Isabel, sister of Sir Ewen Cameron of Locheil. Their second son was Duncan, who took the tack of Auch in Upper Glenorchy.

Tacksmen

The Scottish clan system grew out of an earlier tribal system in the Middle Ages as a response to invasions by Vikings and Normans in the 1100s and 1200s. The Highland clans differed from the feudal systems of England and the Lowlands in that the clan was made up of kin, with the chief as head of the family – the bonds between chief and people were bonds of kinship, not vassalage. The chief granted land to his kin and, while the chiefs may have held their lands by Crown charter, they maintained as much of their independence as they could and managed in the interest of the clan, not the Crown. These lands were central to the clan’s identity; a clan without land was a broken clan.

The clan system persisted so long in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland because of the harsh terrain, which was difficult to move about in and unprofitable to cultivate. For central government, the Scottish Crown, it wasn’t worth the effort to bring it directly under their control. Feudal and more modern social and economic systems were very slow to take hold.

Tacksmen held their lands not by charter but by lease. The tacksman rented the land for well below its economic value, which allowed him to sublease his tack for more than he paid for it and make a living off the difference. The importance of the tacksman to the chief was not a monetary value but rather military, judicial and managerial, managing the farm and the township, manager of people and resources. The tacksman was an integral part of the structure of the clan, the means by which clan and chief maintained control over their land.

However, by the time we have good written records from the 1500s and particularly the 1600s and 1700s the tack system was already beginning to give way before the forces of commercial markets, and chiefs began to ally themselves with the Crown which was making increasing inroads into the Highlands. Contracts were increasingly undertaken between chiefs and individuals rather than within kinship groups. The tacksman’s holding was generally 2½ merkland, a measure of land for which the rent was nominally 1 merk (14 shillings). The tacksman paid a rental in money, produce, and the responsibility to host the chief and his household. In the early 1500s the tack rental was 1 merk / merkland but within 150 or so years this had risen to £30, then £60 or £80. This put considerable strain on the economics of the tack system, especially when the tacksman no longer had his original role in society.

As grazing land became increasingly valuable in the late 17th and 18th centuries, areas that had previously been grazed in common began to be enclosed with dykes – the 1769 tack agreement for Auch between Breadalbane and Patrick required him to build 600 yards of stone fences or ditches a year. In the case of Upper Glenorchy (and elsewhere) the lairds of Breadalbane, beginning with Black Duncan, saw more value in developing deer forests than in farming. There was no future for tacksmen in this new system.

The Campbells at Auch

Auch was a large tack at 8 merkland and the Campbells of Auch also took out other tacks at Breckles, Ardnagaul and other farms, so they were relatively substantial landholders.

Duncan of Auch first married Margaret Stewart and had a son John who seems to have died relatively young. Duncan’s second marriage was to Florence Cameron and had one son, Patrick, and three daughters, Isobel, Margaret and Ann. When Duncan died he was succeeded at Auch by Patrick.

Patrick of Auch married Anne, daughter of John Campbell of Achalader on 24th June 1741. They had at least two sons, John and Colin.

John of Auch married Susan, daughter of William Campbell of Glenfalloch, who was also descended from Black Duncan, in 1780.

The sons of lairds and tacksmen often went into the British army and so tended to marry later in life once they left the service and took up their holdings. Patrick, John and Moses all had military careers prior to taking up their fathers’ tacks. Moses, for instance, was 40 when he married Jessie; she was 20.

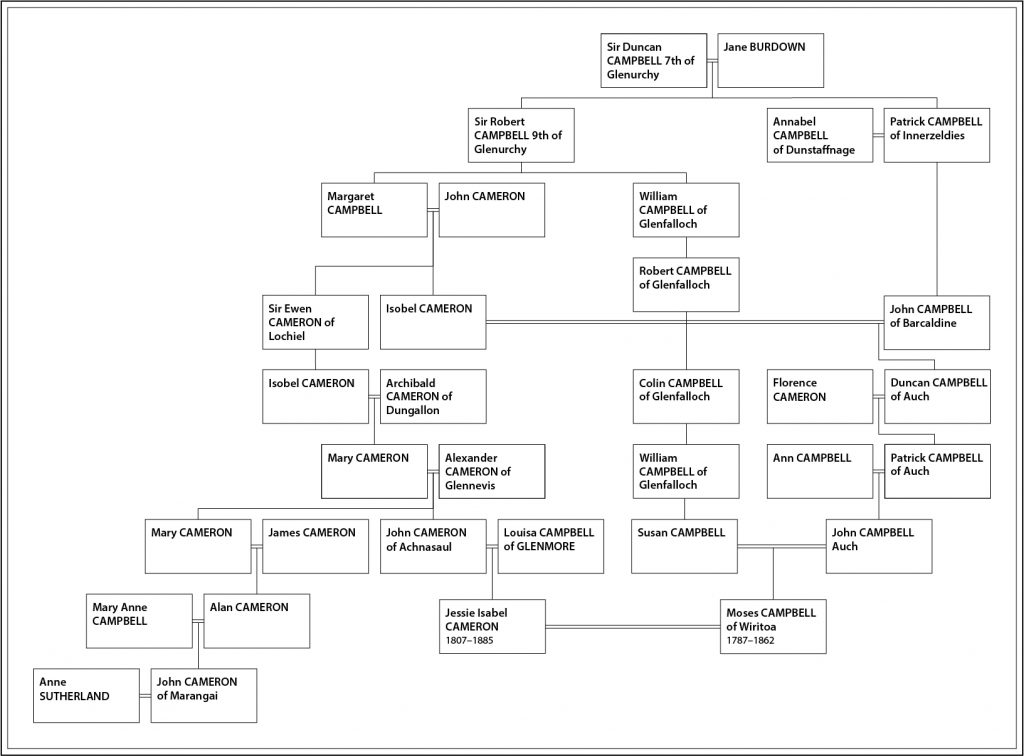

The following family tree shows the relationships between all of these descendants of Black Duncan, and includes John Cameron of Marangai, who immigrated with Moses and Jessie on the Blenheim and was their neighbour at Wiritoa.

Auch, Inverliver and Achindale

By the time John took the tack of Auch it would seem that his situation was no longer economically viable. His solution was to become a freeholder in his own right and buy Inverliver in 1804. While he referred to himself as John Campbell of Auch and Inverliver, it doesn’t appear that he lived there as letters as late as 1827 are addressed to him at Auch. However, whether through bad management or bad luck, this solution never quite worked and John seems to have gotten deeper and deeper in debt.

John and Susan are reputed to have had 21 children, but not all of them survived infancy. The family legend is that Moses owes his name to that high infant mortality rate. He was a very sickly baby and an old nurse said that she could save him if she could name him. Granted permission she pushed a knife into the bible and when it was opened the first name on the page was Moses. Another version of the story has his mother doing the same thing but with her husband’s sword. The story goes on that Susan was so afraid of John’s reaction to the name that she did not tell anyone until they asked for the baby’s name at his christening. One thing is certain; Moses had an intense dislike of his name all his life and was always referred to as Captain Campbell. Even his headstone records him as M. Campbell.

Moses went into the army as a young man, we don’t know when but in 1811 Ensign Moses Campbell was promoted to Lieutenant (without purchase – it isn’t known, but is quite probable, that his father had originally purchased the ensigncy for him). His regiment was the 72nd, the Duke of Albany’s own Highlanders, who served in the Cape Colony (South Africa) from 1816 to 1821. They then returned to Scotland and in 1827 Moses was “on the recruiting Service” in Glasgow when his father summoned him home. The contract between them, dated 13 September 1827, states that “John Campbell is now at a very advanced period of life, unfit for active management of his affairs, and he has on that account prevailed on the said Moses Campbell his eldest Son to relinquish the army and to become resident in the Country.” It was at this time that Moses married Jessie Cameron.

Jessie was born in 1807 and came from a family with a long military history. Her father, John Cameron of Achnasaul, was a Lieutenant Colonel who fought in the American War of Independence and was later Governor of Fort William. Her brother Ewen was a Captain in the 79th regiment. Her most notable ancestor was Sir Ewen Cameron of Lochiel (another descendant of Black Duncan), 17th Chief of Clan Cameron. He was her great, great grandfather and one of the most famous of all highland chiefs. His exploits have been well recorded, probably the most famous being the occasion when, in a life and death struggle with an Englishman, he tore the man’s throat out with his teeth. He said afterwards that it was the sweetest morsel he had ever tasted.

In 1829 Moses took over the farm of Achindale near Fortwilliam, which had previously been held by a Mr Mitchell. Moses was to pay Mitchell the value of the crop already planted, and the arbiters decided that “Captain Campbell of Achindale is to pay Mr. Mitchell, for the beer and oat crop, including straw, the sum of £150 sterling.” Moses complained that this sum included the crop at Donie, which was not part of the original agreement. Unfortunately for Moses, he then went on to slander Mackay, Mitchell’s agent, saying that he was “utterly destitute of the spirit or feelings of a gentleman.” The court awarded Mackay £300 in damages.

Moses, left with a debt burden from his father that he could not service, compounded by the probable failure of the Inverliver venture and his own mismanagement and foolishness, sold up and with his family emigrated to New Zealand. In the end, emigration was the only real solution to the long, slow failure of the tack system.